in this investigation a paint pigment was found to have cu and zn present. what does this suggest?

This projection began with a risk discovery: a saturated, soft blue-light-green background on a limestone funerary stela from the Roman Egyptian town of Terenouthis. Surprisingly, the color was non the same copper-based green found in a bowl too excavated at the site; rather, it was celadonite, the mineral (run into fig. 4.1).1 Most publications on Egyptian materials and techniques provided little information on the use of green earth in Egypt, focusing primarily on materials used during the dynastic periods, when dark-green were not employed. Only a small number of instance studies cited the utilize of green earth on Egyptian artifacts. Curious to discover if there were other instances, I set out on a multiyear research projection to study the use of green pigments in Greco-Roman Egyptian art. This piece of work included an extensive review of existing literature on greenish pigments and a technical survey of artifacts in museum collections, including several at the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The overarching goal of the enquiry was to build a green paint data set that was more than inclusive of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods and to explore changes in pigment use in Egypt over fourth dimension.

| Possible Pigments | Chemical Formulas | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Malachite Verdigris | CuCO3 Cu(OH)2 Cu(CHiiiCOO)2 | Basic copper carbonate and copper acetate minerals |

| Chrysocolla | (Cu,Al)2H2Si2O5(OH)4·nH2O | A naturally occurring copper silicate mineral that frequently occurs with frit |

| Basic copper chlorides | CuiiCl(OH)3 | Described as synthetic pigments in some publications and elsewhere as the alteration products of Egyptian blueish and Egyptian green |

| Organo-copper compounds | Cu-proteinate, Cu-sugar, and Cu-wax pigments | Possible reaction betwixt altered copper-containing pigments and binding media |

| Egyptian bluish Egyptian green | CaCuSi4O10 Cu glass | Synthetic blue and greenish pigments produced past heating sand, natron, flux, and copper minerals |

| Light-green earth | K(Mg,Fe2+)(Fe3+,Al)[Si2Oten](OH)2 (K,Na)(Iron3+,Al,Mg)2(Si,Al)fourO10 | A naturally occurring clay mineral—celadonite and glauconite are the two chief mineral species referenced |

| Mixtures | See description | Combinations of Egyptian blue (CaCuSi4O10), indigo, Egyptian green, orpiment (Equally2Southiii), yellow ochre (Atomic number 262Oiii·H2O), and green earth |

| Possible Pigments | Chemical Formulas | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Malachite Verdigris | CuCO3 Cu(OH)2 Cu(CH3COO)2 | Basic copper carbonate and copper acetate minerals |

| Chrysocolla | (Cu,Al)iiH2Si2Ov(OH)4·nH2O | A naturally occurring copper silicate mineral that oftentimes occurs with frit |

| Bones copper chlorides | Cu2Cl(OH)three | Described every bit constructed pigments in some publications and elsewhere equally the amending products of Egyptian blue and Egyptian greenish |

| Organo-copper compounds | Cu-proteinate, Cu-carbohydrate, and Cu-wax pigments | Possible reaction between altered copper-containing pigments and binding media |

| Egyptian blue Egyptian light-green | CaCuSiivOten Cu glass | Synthetic bluish and green pigments produced by heating sand, natron, flux, and copper minerals |

| Dark-green earth | K(Mg,Fetwo+)(Fe3+,Al)[Si2O10](OH)ii (1000,Na)(Atomic number 263+,Al,Mg)2(Si,Al)4O10 | A naturally occurring dirt mineral—celadonite and glauconite are the two primary mineral species referenced |

| Mixtures | See description | Combinations of Egyptian blue (CaCuSi4O10), indigo, Egyptian dark-green, orpiment (AstwoSouth3), yellow ochre (FeiiOiii·H2O), and light-green earth |

Literature Survey

The literature review focused deliberately on the Ptolemaic and Roman periods—at least initially. To compare paint use during these periods to that of earlier times, the project eventually expanded to include studies focused on dynastic Egypt. A variety of published sources were consulted likewise, as were belittling results reported in the APPEAR database. Antiquity names and , institutions and authors, and pigment characterizations were recorded. The review revealed that a wide range of materials had been used to create the colour light-green in Egyptian fine art. Copper-based green pigments were reported most often and included minerals such every bit and verdigris,2 synthetic pigments such as Egyptian green,iii and alteration products such as copper chlorides and organo-copper compounds.four Green earths and mixtures of blue and yellow pigments were too reported.5 A summary of these pigments is provided in figure 4.1.

Technical Survey

With the help of many collaborators, a technical survey of funerary artifacts was conducted within several Egyptian collections. Artifacts included inscribed stelae, coffins, cartonnage fragments, and painted mummy shrouds. The goal of the survey was to characterize green pigments on artifacts from Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt in particular and, in doing so, increase the number of existing case studies. The results of this survey reflected what was reported in the literature—with 2 important exceptions. First, light-green earth appeared more frequently than copper-based greens on Roman-flow artifacts. Second, a blue-yellow pigment mixture, which has been cited in two previous publications,vi was found on at least 2 (possibly three) artifacts. These findings pointed to changes in paint selection during the Ptolemaic and Roman periods—observations that will be discussed in the conclusions section below. Among the artifacts studied, it was the shrouds that yielded the most interesting results in terms of green pigments identified. The lack of copper greens, forth with evidence of an expanded green palette, make the shrouds the virtually compelling instance studies in terms of greenish color use.

Mummy Shrouds Instance Report

The shrouds (figs. four.2–4.8) are part of the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.seven Like portraits, painted textile mummy shrouds were a course of burial dress for the dead. The shrouds functioned both as role of the mummy's encasement and as a surface for pigment decoration. Sheets of cloth were painted with portraits of the deceased; images, symbols, and writing from both Greek and Egyptian cultural traditions were as well included. The portraits are at times naturalistic, depicting individuals as they were in life, but they can also exist highly stylized, portraying the deceased as an apotheosis of an Egyptian deity.8

Although the bulk of shrouds in museum collections have been separated from the body, their overall shape, positioning of painted images and framing elements, wear patterns, and staining attest to their original use every bit mummy wrappings.9 The shrouds discussed in this newspaper, although fragmented, stand for a number of portrait formats. These include the bust-length vignette format, in which the portrait is limited to the private's upper body; the total-length portrait; the three-effigy format, in which the deceased is flanked by deities such equally Osiris and Anubis; and shrouds in which the deceased is portrayed as a deity.ten The sections that follow will briefly describe each shroud.

Getty Museum

Two vignette-type shrouds from the J. Paul Getty Museum were analyzed. The painted portrait of a boy depicts a young man with a falcon on his left shoulder (see fig. iv.2). The painting ends just below the youth's shoulders, indicating that the shroud would have been placed over the face of the deceased and secured with wrappings in the same mode as a portrait console. The green of the leaves in the is strikingly bright, and upon close test 1 can observe bright yellowish pigment particles, indicating that the paint is some kind of mixture.11

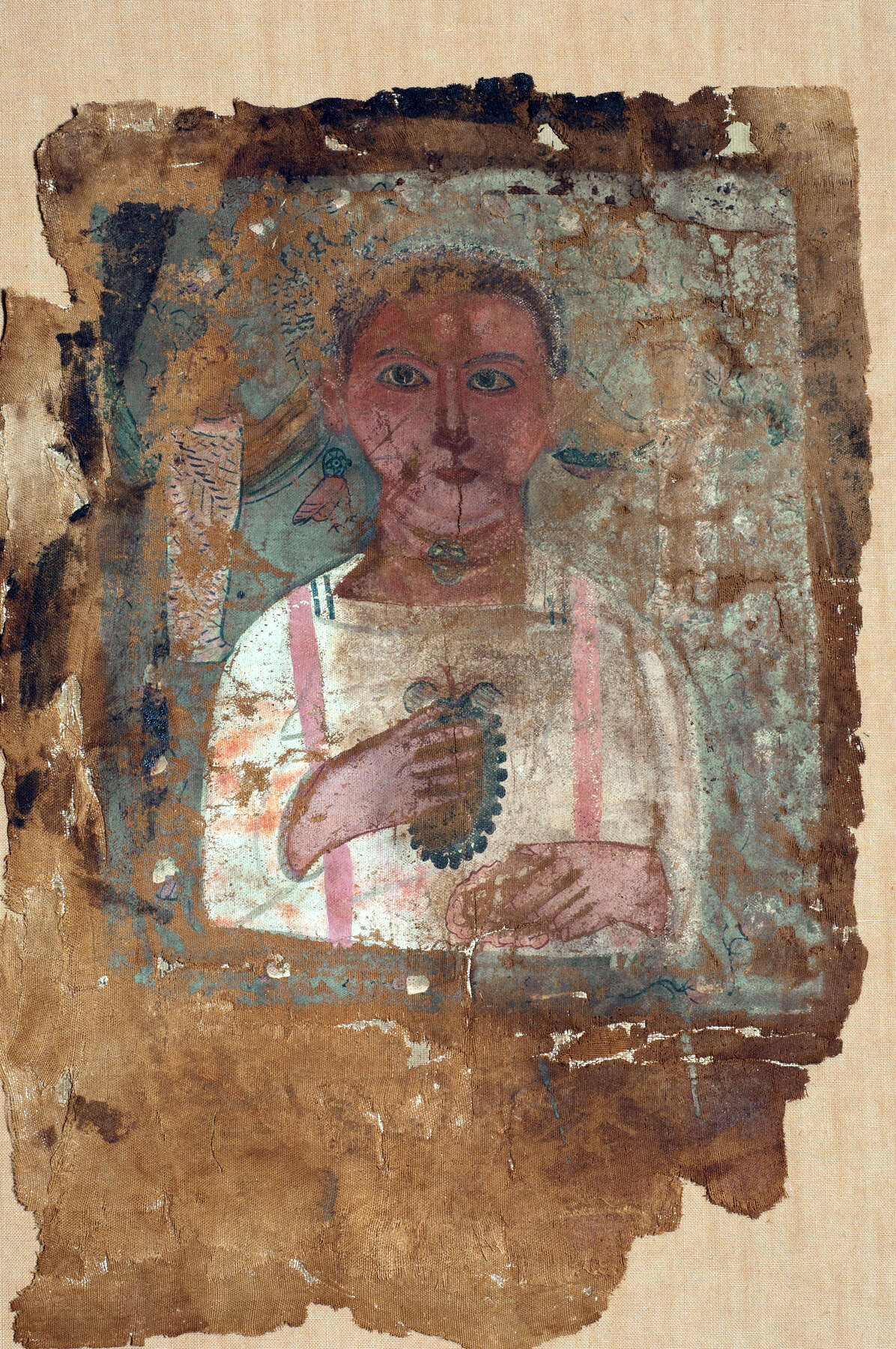

The painted portrait of a youth features a boy holding a floral and a cluster of grapes (encounter fig. 4.three). A falcon and a mummiform effigy appear over his proper correct shoulder. Visible in the fly to the boy's left is a stripe of light-green; it appears to have been rendered by layering blueish pigment over yellow pigment.

Effigy iv.two

Effigy iv.two

Figure 4.three

Figure 4.three

Metropolitan Museum

4 painted shroud fragments were analyzed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. One instance is a fragment of what was likely a total-length portrait shroud of a woman (see fig. 4.4). Only the adult female's beringed hands and a pink floral garland remain. The leaves in the garland are rendered in dark blue or black, pale blue, and dark-green.

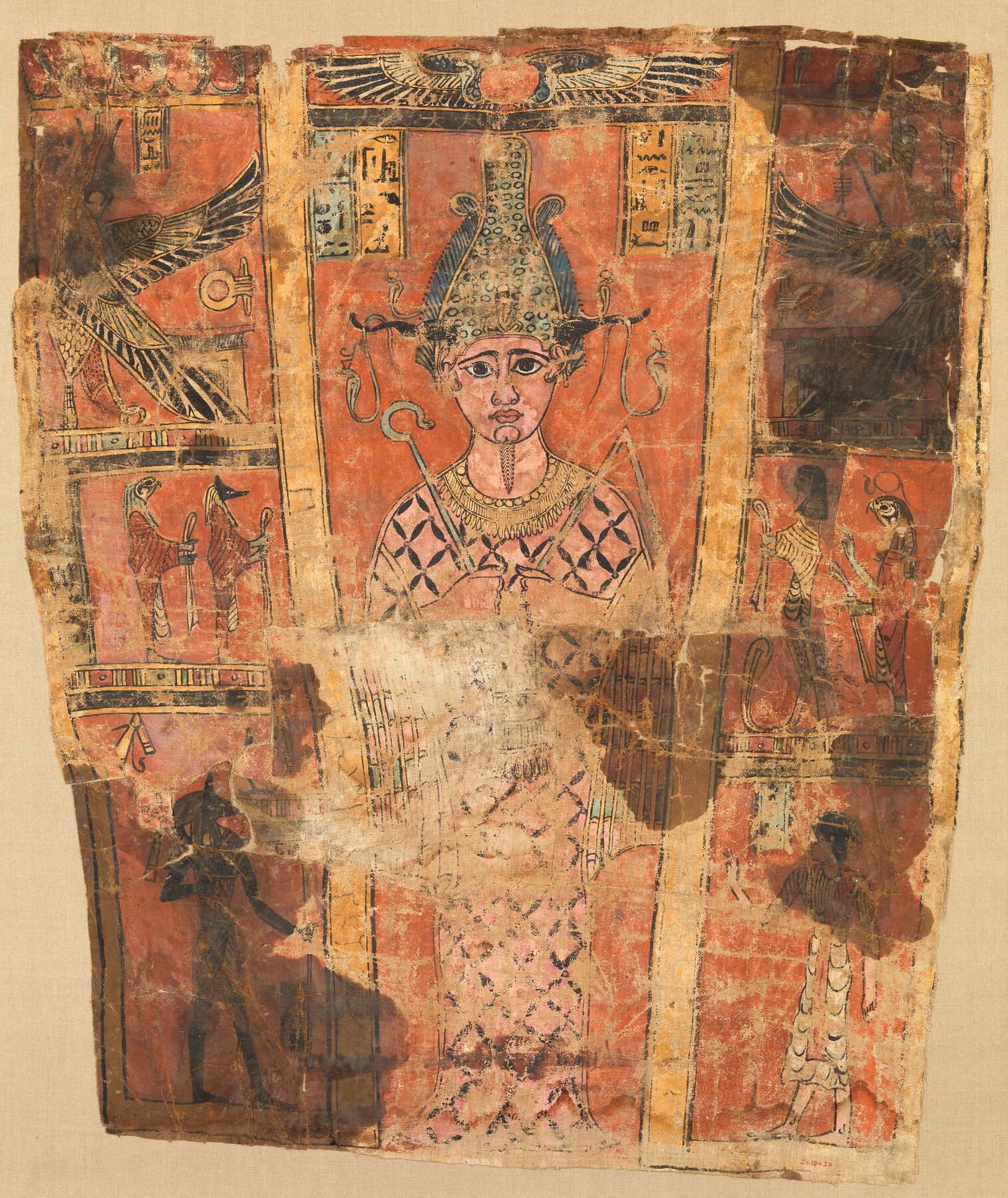

Another example is a full-length portrait shroud of a young man who takes the form of Osiris (see fig. 4.v). The figure is enshrined inside an architectural framework crowned by an uraeus. Half-dozen adjacent registers depict Horus, Anubis, Ra-Horakhty, and a portrait of the deceased.12 The figure's crown and crook as well as ii of the hieroglyph registers are rendered in a stake turquoise color.

Figure 4.four

Figure 4.four

Effigy 4.5

Effigy 4.5

Two other fragments come from what appears to exist an Osiris shroud. Fragment A (come across fig. four.6) shows the right shoulder of a mummiform figure covered with a dewdrop cyberspace. The figure wears a wide collar and a wadjet eye amulet, and an unknown geometric course sits on the netting. Fragment B (see fig. 4.seven) portrays a falcon head. The shroud fragments' backgrounds are a colorful brandish of checkered patterning. One checky department is rendered in yellow-green and dark green—the same dark green seen in the upper portion of the broad collar, in the unidentified geometric grade, and beneath the falcon. The xanthous-green checkerboard appears to take been made by superimposing xanthous squares over a dark green background.

Figure iv.6

Figure iv.6

Figure 4.vii

Figure 4.vii

2 painted shroud fragments (66.99.141 and 66.99.140—not pictured) were probable in one case part of a larger shroud (come across fig. four.eight). The onetime depicts a female deity, peradventure Nephthys, whose sheath dress appears to be greenish, making this shroud of interest to the report. The following sections discuss the techniques used to characterize the green pigments found on all the shrouds.

Effigy 4.viii

Effigy 4.viii

Green Pigment Characterization

Egyptian green pigments are notoriously hard to characterize—and visually identify—for several reasons. Get-go, the aging and darkening of can cause bluish pigments to appear increasingly green over time. Another challenge is the fact that certain green pigments (such as malachite, copper chlorides, and organo-copper compounds) tin can be alteration products, making information technology hard to conclude that an expanse was intended to be green at all. Finally, greens are often the effect of pigment mixtures, significant that multiple components must be characterized in society to make a full identification.

Technical Examination

Because of these challenges, a range of analytical techniques was used to investigate shroud paint surfaces and identify pigments in paint dispersions and cross sections: using Bruker Tracer Three-V handheld XRF units with Rd tubes gear up to 40kV, 12.50μA at thirty-second run times with S1PXRF software; using a Hyperion 3000 FTIR spectrometer in transmission style, with scans from 4000 to 600 inverse centimeters; using a Renishaw arrangement equipped with an He-Ne light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation, with an emission line set at 633 nanometers; and finally, using a Philips XL30 ecology scanning electron microscope with Oxford INCA software. The analysis was made possible by the Getty Conservation Plant and the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Scientific Research Department.

As the inquiry progressed, it became clear how unlike techniques could be used to reply specific questions most the greens. For example, XRF could narrow the possibilities based on elements nowadays; SEM-EDS and Raman spectroscopy, thanks to their bespeak-identification capability, were especially helpful for identifying the components of mixtures. It should exist noted that, subsequent to my research at the Getty, boosted analyses were carried out on shrouds 75.AP.87 and 79.AP.219 (see figs. 4.2 and 4.iii). They included multispectral imaging, , XRF scanning,13 combined XRF/ analysis,14 and of many areas of color,15 including green.

Multispectral Imaging

was also used to investigate the shrouds' paint surfaces. Over the by decade MSI has emerged every bit a valuable tool for examining and characterizing pigment surfaces.16 This photographic technique captures the feature reflectance, assimilation, and brilliance properties of pigments and other materials in an image. Because information technology can be carried out using a modified DSLR camera, MSI is too a relatively accessible tool in terms of cost.

The imaging method used to examine the shrouds was adapted from a technical imaging manual developed at the British Museum. This manual provides step-by-step instructions for capturing images in visible, and , , and modes, equally well as guidelines for paradigm scale.17 A Nikon D70s UV/IR photographic camera contradistinct to record the electromagnetic spectrum between 250 and 1100 nanometers was used for image capture, as were lite sources, lens filters, and calibration standards recommended in the British Museum manual. An open up-source calibration workspace developed past the manual's authors was used to generate standardized multispectral images that can be more readily compared with those obtained under dissimilar conditions.

A set of reference paint-outs was created and imaged to provide a centralized visual record of the reflectance, assimilation, and luminescence properties of known aboriginal pigments and binders. The pigment-outs have been a useful tool for interpreting the MSI images of artifact paint surfaces and for isolating the particular imaging characteristics of copper-, world-, and -based green pigments in various binding media. Certain imaging techniques proved peculiarly valuable in the investigation of the shrouds. For example, 1 could often differentiate between copper-based greens and light-green earths past the relative darkness of copper greens in UVL images,18 compared with dark-green earths. The presence of a red infrared fake colour, forth with the absence of luminescence in VIL images in green areas on shrouds X.491A and 10.491B (see figs. iv.six and 4.7), indicated that this pigment mixture included indigo. Used in this style, MSI provided important initial information that guided subsequent analysis and data interpretation.

Results

The results of the scientific investigation of the shrouds are summarized in figure four.9. Information gathered by projection collaborators and other scholars is cited in the text.

| Shroud | Analysis | Characterization |

|---|---|---|

| 75.AP.87 | XRF: Ca, Fe, Pb, As peaks XRF mapping: high As counts in leavesnineteen SEM-EDS: Ca, Si, S, Atomic number 82, and Equally identified in individual pigment particles in green paint cross section Raman: indigo and orpiment identified in point ID of blue and yellow areas of sample cantankerous sectiontwenty PLM, infrared imaging confirm presence of indigo, orpiment in leaves21 | Vergaut |

| 79.AP.219 | XRF: Fe, Atomic number 82, As peaks XRF mapping: high As counts in drapery above bird22 FORS: indigo detected23 Infrared imaging indicates presence of indigo in green section of drapery, suggesting that indigo and orpiment were layered to course dark-green24 | Indigo and orpiment, layered or in a mixture |

| X.390 | XRF: n/a FTIR: calcite and celadonite25 Imaging: pale bluish areas of leaves comprise Egyptian blue; green sample expanse has IRRFC similar to Republic of cyprus dark-green earth (celadonite)26 | Green earth (celadonite?) |

| 25.184.20 | XRF: Ca, Fe, Every bit, Pb (Every bit may be Pb L alpha peak) FTIR: calcite and celadonite27 Imaging: pale turquoise areas have muted blue IRRFC similar to Republic of cyprus greenish world (celadonite); depression absorption of same areas in UVL image suggests that pigment is not copper based | Green earth (celadonite?) |

| X.491A–B | XRF: Ca, Fe, As FTIR: calcite, indigo, Egyptian dark-green (?);28 orpiment (acme at 800 cm-ane)? Imaging: night green squares are cerise in IRRFC, consistent with indigo; yellowish-green squares painted over background have pale yellow IRRFC, consistent with reference orpiment paint-outs | Vergaut? |

| 66.99.141 | XRF: Ca, Fe, Cu, As, Atomic number 82 (Every bit may be Pb L alpha pinnacle) FTIR: Egyptian blue29 VIL imaging confirms that "greenish" clothes is Egyptian blue | Darkened Egyptian blue |

| Shroud | Analysis | Label |

|---|---|---|

| 75.AP.87 | XRF: Ca, Fe, Pb, Every bit peaks XRF mapping: high As counts in leaves 19 SEM-EDS: Ca, Si, S, Atomic number 82, and Every bit identified in private pigment particles in green paint cross section Raman: indigo and orpiment identified in point ID of blueish and yellow areas of sample cross section 20 PLM, infrared imaging confirm presence of indigo, orpiment in leaves 21 | Vergaut |

| 79.AP.219 | XRF: Fe, Lead, As peaks XRF mapping: high Equally counts in drapery above bird 22 FORS: indigo detected 23 Infrared imaging indicates presence of indigo in green section of curtain, suggesting that indigo and orpiment were layered to form dark-green 24 | Indigo and orpiment, layered or in a mixture |

| Ten.390 | XRF: n/a FTIR: calcite and celadonite 25 Imaging: pale blue areas of leaves contain Egyptian blue; light-green sample area has IRRFC like to Cyprus green world (celadonite) 26 | Green earth (celadonite?) |

| 25.184.twenty | XRF: Ca, Fe, Equally, Pb (As may be Lead L alpha peak) FTIR: calcite and celadonite 27 Imaging: stake turquoise areas have muted blue IRRFC like to Republic of cyprus green earth (celadonite); low absorption of same areas in UVL image suggests that paint is not copper based | Light-green world (celadonite?) |

| 10.491A–B | XRF: Ca, Fe, As FTIR: calcite, indigo, Egyptian green (?); 28 orpiment (acme at 800 cm-1)? Imaging: nighttime green squares are carmine in IRRFC, consistent with indigo; xanthous-dark-green squares painted over groundwork have pale yellow IRRFC, consequent with reference orpiment pigment-outs | Vergaut? |

| 66.99.141 | XRF: Ca, Fe, Cu, Every bit, Pb (Every bit may be Lead L blastoff peak) FTIR: Egyptian bluish 29 VIL imaging confirms that "green" dress is Egyptian blue | Darkened Egyptian blue |

For the Getty objects, XRF assay of leaves in shroud 75.AP.87 (run into fig. four.2) showed peaks for calcium, iron, lead, and—notably—arsenic, the results of which are confirmed in 10-ray maps acquired from the shroud subsequent to this project.30 SEM-EDS assay identified both sulfur and arsenic in private pigment particles in a green paint cross section taken from a leaf. An additional paint cantankerous department from the same area revealed particles of and indigo,31 confirming that the greenish pigment used in the wreath is vergaut, a mixture of the organic blue pigment indigo and the arsenic-sulfide mineral orpiment.32

Shroud 79.AP.219 (run into fig. 4.iii) was analyzed with XRF in the green-colored center section of the fly to the boy's right (fig. four.10). This analysis yielded XRF peaks for fe, lead, and arsenic. High levels of arsenic were too detected in XRF maps of both the yellow and dark-green sections of the wing.33 FORS assay conducted subsequent to this research detected indigo in the lower department of the wing, indicating that a combination of indigo and orpiment was likely used to create the greenish colour.34 The green itself appears to exist a effect of overlap between a stripe of orpiment and a stripe of indigo, although it could also be a mixture of the two pigments; further analysis—such as Raman spectroscopy of a paint cantankerous section—would be needed to ostend.

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10

At the Metropolitan Museum, a sample of green paint was taken from the garland on shroud X.390 (see fig. four.4). FTIR analysis yielded a good friction match for green earth—particularly celadonite.35 This lucifer was further supported by the technical imaging results, in which the infrared faux color of the sample surface area is similar to reference false colors of Cyprus green world, which has been previously characterized as being predominantly celadonite.36

The Osiris shroud 25.184.20 (see fig. 4.5) was analyzed with XRF in ane of several turquoise painted areas. Interestingly, no copper was found in the XRF spectra, which ruled out the possibility that this could be a green frit. FTIR assay instead suggested that the turquoise colour is green earth, a pigment that tin carry a wide range of hues from olive green to pale turquoise. The best match to this shroud'south sample was, every bit in the previous example, celadonite. The imaging supports this event, as does the relatively low assimilation of the turquoise areas in the UVL image.

The results for shroud X.491A and B (see figs. 4.6 and 4.vii) are less straightforward, but the materials present advise that the creative person used a mixture to produce green. The get-go clue was the meaning arsenic peak in the XRF spectrum taken from a night green area in the checkerboard blueprint behind and to the right of the effigy (meet fig. iv.eleven). Multiple FTIR spectra were gathered from a sample taken from the same dark green foursquare. Although one such square indicated a possible friction match for Egyptian dark-green, the lack of copper in the XRF spectrum acquired in the same area likely rules out its presence. A second FTIR spectrum was generated from the same sample, one that indicated a match for indigo. Could this, in fact, be a mixture of indigo and a yellow pigment? The imaging supports this interpretation, as the green area in question is ruddy (indicating indigo) in the IRRFC images; information technology also suggests that a layer of orpiment was applied over this dark light-green mixture to create the light green squares in the same checkerboard pattern. These areas announced bright pale yellow in the IRRFC image—as practice other areas of brilliant xanthous color on the portrait. Follow-up assay with Raman spectroscopy would assist to confirm this hypothesis.

Figure 4.11

Figure 4.11

The FTIR results from shroud 66.99.141 (run across fig. 4.8) strongly indicate that the goddess's "light-green" dress is, in fact, a discolored Egyptian blue. VIL imaging showed a stiff infrared brilliance throughout the clothes, helping to confirm the spectroscopic results.

Discussion

The technical investigation of the shrouds and of other artifacts included in the survey demonstrates how accessible imaging tools tin optimize the investigative potential of traditional analytical techniques. In this study, multispectral imaging and analysis informed each other; together, they non only helped confirm ambiguous characterizations but too provided a broader impression of how pigments were used across an artifact's surface. These combined techniques were peculiarly useful in analyzing the shrouds, where green, bluish, and xanthous pigments are often mixed and layered.

The alien results seen with fragments X.491 A and 10.491B (see figs. 4.6 and 4.seven) help illustrate the fabric and chemical complexity of green pigments and mixtures. Although the FTIR spectrum indicates a possible match for Egyptian dark-green in the sampled area shown in effigy 4.11, the lack of copper in the XRF spectrum acquired in the aforementioned area rules out its presence. Likewise, peaks at 1627, 1462, and 1076 inverse centimeters appear to exist from indigo, while a superlative well-nigh 800 inverse centimeters in spectra from both dark and light green squares could be from orpiment, the latter being consistent with the significant XRF pinnacle for arsenic in the same expanse. Raman spectroscopy would be needed to confirm that this colour is, in fact, a mixture of indigo and orpiment (vergaut).

While questions remain about the exact character of two of the shrouds' green pigments, it is noteworthy that the simply copper-containing pigment found on the shrouds was a discolored Egyptian blue that appeared green. Although copper-based greens connected to be used later on the dynastic periods, their absenteeism on the shrouds is interesting and reflects a diversification in green pigment use during Egypt's Ptolemaic and Roman periods. This shift in pigment selection is suggested non only past the use of vergaut but also by green earth pigments—their all-time-known mineral deposits were located outside of Arab republic of egypt,37 and their use on these artifacts offers intriguing concrete testify of extensive paint trade networks within the Hellenistic and Roman worlds.

Conclusions

The technical study of the painted mummy shrouds provides a small but meaningful addition to a growing Egyptian paint data ready. These and other studies are helping to create a more than inclusive knowledge base on Egyptian materials and engineering—one that focuses increasingly on the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. The research here demonstrates the sheer variety of greens that may be encountered on an antiquity besides equally the range of analytical tools that are required for light-green pigment identification. These analyses also prove how pigment choices expanded during Egypt's Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

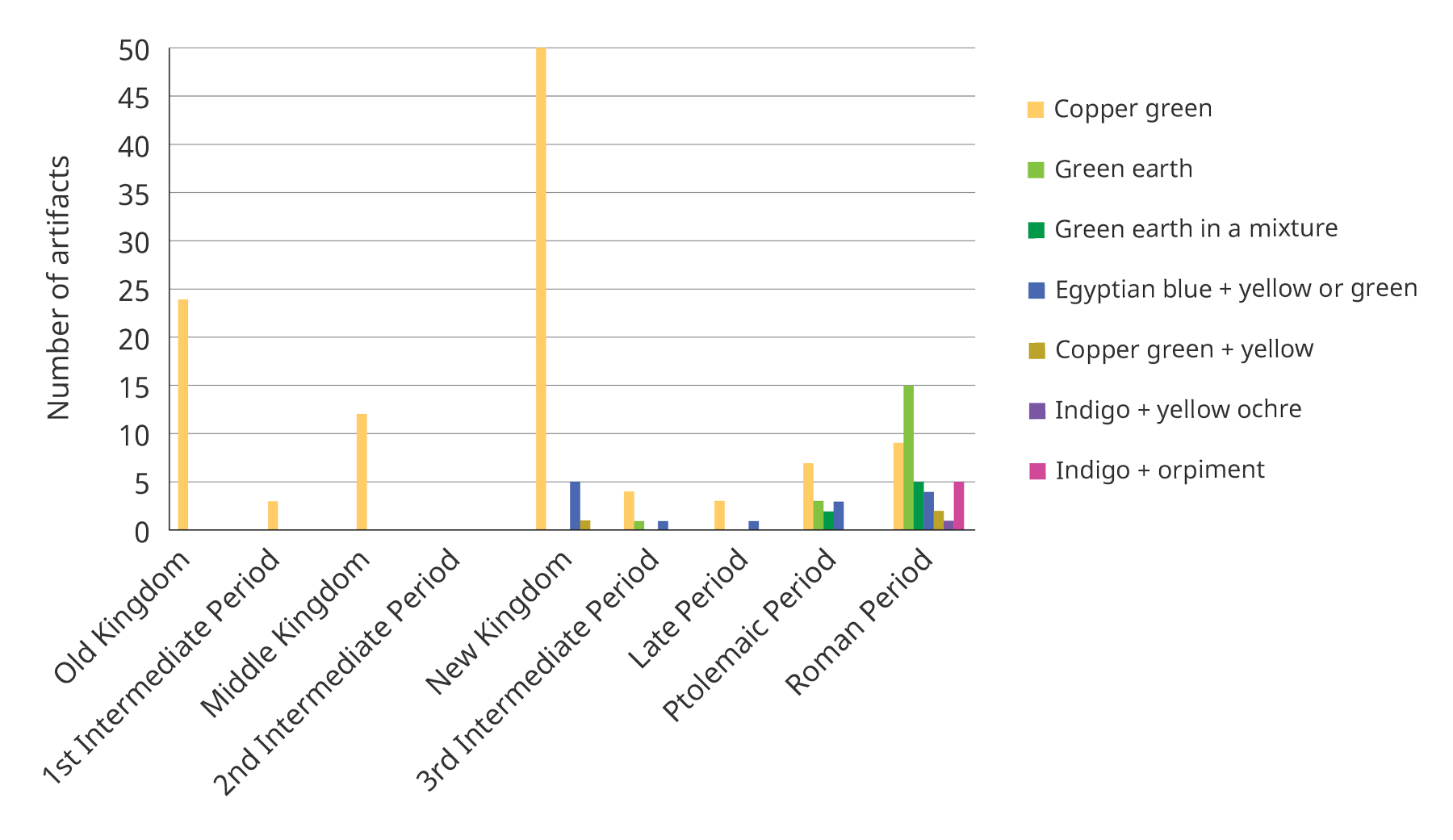

Plotting the results of this projection's technical survey graphically (fig. 4.12), helps visualize this shift in green paint employ. In comparing the types of greenish found on Ptolemaic and Roman Egyptian artifacts with earlier uses of green, one tin can readily see an expansion in the types of green pigments and combinations of pigments used to achieve the colour. Occurrences of green earth become much more than common in the Roman period and at this time are found on artifacts more frequently than copper-based greens. Mixtures, likewise, occur more frequently, and mixtures of indigo and yellow occur exclusively during the Roman period.

Figure iv.12

Figure iv.12

This expansion of the dark-green pigment palette coincides with the introduction of traditionally Hellenistic and Roman pigments into Arab republic of egypt, such every bit rose and .38 Green world, besides, originates in the Hellenistic paint tradition, and its utilize appears well established by the time portrait panels and shrouds were in demand.39 The utilise of blue and yellow mixtures, although present in earlier dynastic Egyptian technical studies, appears to accelerate during the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. With an increasingly various palette came many possible green hues and shades and, as seen on a number of the shrouds, a propensity for mixing, layering, and experimenting with color. In portraiture in full general, this nuanced use of colour is reflected in both artists' painting techniques and choice of materials.forty

The appearance of vergaut is also interesting (fig. 4.13). Perhaps best known for its employ in Islamic and Western European illuminated manuscripts, vergaut is mentioned in Eraclius'southward tenth-century treatise De coloribus et artibus Romanorum and has appeared on many painted wooden artifacts and shrouds from Egypt and other Roman provinces.41 More examples are sure to emerge as scholars proceed to written report artifacts from this syncretic period of Egyptian culture; making this bear witness widely available is crucial to building complete pigment characterizations, agreement cloth choices and changes in artistic practice, and providing more, much-needed, technical information about Greco-Roman Egyptian art.

Figure 4.xiii

Figure 4.xiii

Acknowledgments

This inquiry is the product of the collaborative effort of many individuals who have lent their time, expertise, and support to the project over many years. For supervising my fellowship research on dark-green pigments I would similar to thank Suzanne Davis and Claudia Chemello at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology; Marie Svoboda and Jerry Podany at the J. Paul Getty Museum; and Ann Heywood at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I would also like to give thanks Emilia Cortes and the Metropolitan Museum's Egyptian Art Department and Greek and Roman Art Department for supporting my inquiry on the shrouds. I am indebted to many scientists for their help and analysis at both the Getty Conservation Found and the Metropolitan Museum's Department of Scientific Research, specifically Julie Arslanoglu, Federico Caro, Ilaria Ciancetta, Giacomo Chiari, Art Kaplan, Elisa Maupas, Adriana Rizzo, Karen Trentelman, and Marc Walton. Many thanks as well to Monica Ganio and David Strivay for making the results of their subsequent analyses of the Getty shrouds bachelor. I must also thank Joanne Dyer for her MSI expertise, likewise as Anna Serotta and Dawn Kriss for their ongoing collaborative back up with reference standards, VIL methodology, and more than. Finally, many thanks to J. P. Brownish, Laura D'Alessandro, Emily Heye, and Tina March for accommodating my enquiry at their museums.

Notes

© 2020 Caroline Roberts. Originally published in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project © 2020 J. Paul Getty Trust, www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits (licensed under CC By 4.0).

Source: https://www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits/part-one/4/

0 Response to "in this investigation a paint pigment was found to have cu and zn present. what does this suggest?"

Post a Comment